MORE THAN PROFIT: Network Economies

| Site: | GEN Europe's learning platform |

| Course: | Launch & Thrive Online Learning Package |

| Book: | MORE THAN PROFIT: Network Economies |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Tuesday, 28 October 2025, 6:27 PM |

Description

1. What are "Economies"?

This part of the module might seem quite specific, but in reality, it is a very holistic and general area of learning! If you expect that there will be an explanation of such notions as Trade, Markets, Industries, Commerce, Business, Money, Currency, GDP, Inflation, Employment, Investments, Consumption, and Production... you might be a bit disappointed! It is true that those phenomena influence your Network and yourself in the World. Nevertheless, the word "economy" has its origins in ancient Greek. It comes from the Greek word "oikonomia" (οἰκονομία), which is a combination of two words: "oikos" (οἶκος), meaning "house" or "household," and "nomos" (νόμος), meaning "law," "custom," or "management."

Originally, "oikonomia" referred to the management and administration of a household or a family estate. It involved the organization of resources, labour, and finances within a household to ensure the well-being and prosperity of its members.

Today, "economy" is a central concept in the field of economics, which studies how societies allocate scarce resources to satisfy human wants and needs. Here, we would like to reconnect to the original meaning of the word "economy" and even talk about many different "economies" as stated in the title of this chapter.

Therefore we will mention words such as Finance, Care, Gift Economy, Circulation of Goods, Empowerment, Barter and more... which are related to understanding economies as care for the common good.

In this part, you will:

♥ learn about the approaches to the economy known in the ecovillage and sustainable communities movement

♥ get interesting tools to introduce the topic of economy to your network

♥ get rid of the fear of the word "economy" and understand why it is important to maintain stability in the ecovillage network.

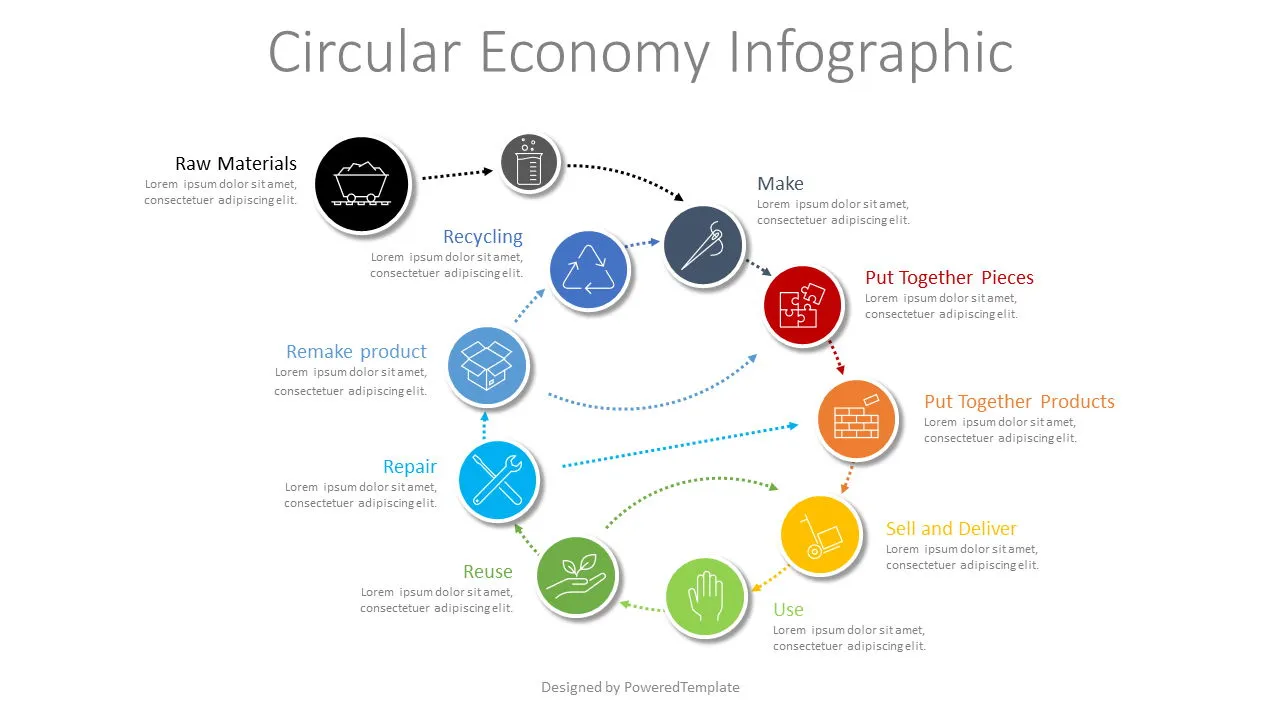

2. Circular economy

The circular economy is an economic model that aims to minimize waste and make the most of resources by keeping them in use for as long as possible. It involves regenerating and restoring natural systems while also creating social benefits. The circular economy within the ecovillages network emphasizes creating resilient, inclusive, and harmonious systems that benefit both people and the environment. The circular economy within a social permaculture approach combines the principles of circular economy with the ethics and practices of permaculture, with a strong emphasis on community and social well-being. This approach seeks to create sustainable and regenerative systems that not only minimize waste and resource depletion but also prioritize social equity, community resilience, and holistic well-being.

3. Gift Economy

In the realm of building a gift economy culture, the seven rules articulated by the German/Brazilian Dragon Dreaming Trainer, Ita Gabert, offer a profound guide for fostering a society based on generosity and mutual support. These rules encapsulate the essence of social permaculture, where the interconnectedness of individuals and communities is nurtured, much like the delicate balance of a thriving ecosystem.

Social permaculture, at its core, encourages us to cultivate harmonious relationships and design systems that benefit all members of our communities. Ita Gabert's rules align beautifully with this concept, emphasizing principles such as honesty, care, and selflessness. They remind us that in a gift economy, the act of giving is not solely about material exchanges but also about recognizing the inherent worth in what we share and fostering genuine connections.

SEVEN RULES FOR GIFT-ECONOMY:

- Be honest, just ask for or accept what you need.

- Be aware, of how much lovely work is in the things you got - honour and care for it accordingly.

- Pass on as a gift to another, all that you don’t need anymore.

- Whatever you make or do, put your lifeblood in it and give it - let it go.

- Look to the eyes when you give something, look to the eyes when you get something, and make of it a real meeting.

- Be aware that when someone is giving, she or he is already getting something very precious - don’t over-celebrate (effusive-exaggerate) if you get it, but honour it appropriately.

- Watch your emotions. If you find some greed, envy or egoism in you in either giving or getting - send these feelings in yourself, a smile.

The true gift is not merely a back-and-forth between individuals. A Buddhist tale tells of two who did this, and after their death, they were transformed into poisoned wells. A true gift is given selflessly as a result of fostering compassion through assisting in meeting the needs of others – a gift of time, money or even just attention. Ultimately gift giving is the source of all scientific and technical progress, where rather than “intellectual property” to be sold to the highest bidder, we community our discoveries by giving them away through meetings, conferences or publications. A true gift is given by the giver out of gratitude, not out of obligation, it is a part of celebrating who I am and who you are.

As we delve deeper into the discussion on key staff members involved in projects, it becomes evident how these principles can guide the competencies and experiences of individuals, enabling them to create meaningful and sustainable initiatives that resonate with the essence of a gift economy.

4. Empowered fundraising

Because of our monetary caused wounds, suffered at the hands of the ways we use money, it is all too often the case that an individual feels that a person who declines to make a contribution and who says “No” when asked, is in some way rejecting the person asking by rejecting the values of the person who is asking. It is easy to internalize this as a negative feeling. The secret to empowered fundraising is to have the “No” have the same meaning as a “Yes”, as both are an opportunity to establish a deeper relationship with that person, a relationship based upon value rather than upon superficial interests held in common. In asking you are offering a genuine invitation to become involved, and an authentic invitation is based equally upon the power to decline as to accept. Being disappointed by the “no” response will always be communicated in one’s body language, and this acts as a form of coercion that aims, rather than an invitation, as a form of manipulation, to get the person to say “yes”. This is also motivated by our “scarcity consciousness” and is a form of disempowerment.

When given a “No”, however, the person involved should always follow up with three further questions.

- Could I ask “Why”? We are sincerely interested in learning the reasons why people either accept or decline our invitation, and our offer to participate.

- Would you like us to ensure that you are to be kept informed about how this project is going?

- Do you know anyone else who may be interested in such a project, to whom you could introduce us?

Once again, there should be no obligation for anyone to answer these questions, as any sense of obligation will ultimately backfire upon the project. A dissatisfied person will tend to tell many more people than one who is satisfied in such circumstances.

This exchange of information about the project will keep the community relationships alive, and may, at a future date, lead to a person who originally declines the offer to engage with the project, to participate in some other, perhaps even more valuable, way.

4.1. Tool: Face-to-face empowerment

Face-to-face empowerment

Introduction:

Successful fundraising is a direct outcome of building genuine, face-to-face connections with individuals. It thrives on personal relationships, rather than the impersonal methods of cold door-knocking or telephone inquiries. While phone calls do have their place, they should primarily serve as a means to arrange meaningful in-person meetings or meetups at a mutually convenient location. In these interactions, the foundation is always an existing depth of friendship, intimacy, or acquaintance, where you are not a stranger to the person you are reaching out to.

So, where do we go from here? After each participating member has contributed their balance-point contribution to the project, each participant takes the following steps:

Step 1: Identifying Your Network

Participants are encouraged to compile a list of ten individuals from their personal network, which may include family, friends, colleagues, or acquaintances. These are individuals they intend to approach within the next three weeks. Based on the nature of their existing relationships, each participant estimates what they believe the person's balance point might be. The balance point represents the amount they will be asked for. It's worth noting that the accuracy of this assessment matters less at this stage, as individuals will have the freedom to adjust their contributions when the actual approach is made.

Step 2: Identifying the First Three

After creating their lists, participants then choose the first three people they plan to approach within the next week. They pair up with a fellow participant to engage in role-playing exercises. The initial focus of these exercises is to share with their partner details about the relationship they have with the person they intend to approach, along with the circumstances surrounding the forthcoming request. This sharing allows their partner to empathize with the character of the person being approached and envision potential responses.

Step 3: The Approach

When asking an individual for their support, participants follow these key steps:

- Begin by ensuring a clear understanding of the project's nature and significance.

- Establish early on that you are inviting the person to become an active participant in the project.

- Introduce the concept of "empowered fundraising" and explain the notion of the "balance point."

- State the estimated balance point, for instance, $XXX, and request their contribution. After making the request, maintain silence, allowing the person to respond without interruption.

Step 4: Response and Follow-up

At this juncture, the person approached may choose to accept, adjust, or decline the requested contribution. Regardless of the outcome, participants are encouraged to accept the response gracefully. Following this interaction, three essential questions are posed:

- "May I ask why?" to gain insights into the reasons behind their decision.

- "Would you like to stay informed about the project's progress?"

- "Do you know anyone else who might be interested in our project?"

If the person accepts the invitation, participants can share what they've learned through the workshop and extend an invitation to participate in relevant training events.

Step 5: Debrief and Reflection

Both participants in the role-play debriefed on their experiences. They explore the feelings that arose during the request and evaluate the openness, honesty, and authenticity of the invitation. They also identify areas for improvement.

Conclusion: Building a Support Team

The final step is to create a support team for those making the requests. Participants designate a "buddy" with whom they've role-played. Contact details are exchanged, and participants commit to engaging with their buddy to share their approach experience and outcomes at a mutually convenient time. Additionally, a record is kept of the names and requested amounts, which, when totalled, provide an estimate of the potential funds that may result over the next three weeks from the Empowered Fundraising approach. Remarkably, participants often find themselves pleasantly surprised by the generosity that can emerge through this process.

4.2. Tool: NIST Economic Decision Guide Software

The link to the digital tool:

https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/SpecialPublications/NIST.SP.1197.pdf

The Economic Decision Guide Software (EDGe$) Tool brings to your fingertips a powerful technique for selecting cost-effective community resilience projects. This decision support software is designed to support those engaged in community-level resilience planning, including community planners and resilience officers, as well as economic development, budget, and public works officials. It provides a standard economic methodology for evaluating investment decisions required to improve the ability of communities to adapt to, withstand, and quickly recover from natural, technological, and human-caused disruptive events. The tool helps to identify and compare the relevant present and future resilience costs and benefits associated with new capital investment versus maintaining a community’s status quo. The benefits include cost savings and damage loss avoidance because enhancing resilience on a community scale creates value, including co-benefits, even if a hazard event does not strike.

Introduction

‘Economic Guide’ develops economic decision guidance for the evaluation of alternate investments designed to improve community resilience through strengthening the ability to respond, withstand, and recover from disruptive events. It is designed to implement the principles and attributes of resilient communities upon which enhanced resilience may be developed, evaluated, and implemented. A common attribute of resilient communities is risk management through an integrated approach to managing threats and opportunities for decision-making that is balanced and informed. Developed at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), this guide will assist users of the Community Resilience Planning Guide for Buildings and Infrastructure Systems (‘Planning Guide’) in understanding the benefits, costs, and tradeoffs involved in making capital improvements to the built environment for increased resilience, recognizing the key roles buildings and infrastructure systems play in supporting the social functions of a community. The guidance follow industry-standard economic methods, ensuring that different analyses of alternative infrastructure investments can be compared with each other and to a business-as-usual baseline.

Purpose

There is an abundance of research focused on topics related to community resilience, including best practices for community assessment; however, guidance is needed to evaluate the economic

ramifications of investment decisions into capital infrastructure to improve community resilience. The purpose of this report is to provide a standard economic methodology for evaluating investment decisions aimed at improving the ability of communities to adapt to, withstand, and quickly recover from disasters.

The Economic Guide frames the economic decision process by identifying and comparing the relevant present and future streams of costs and benefits to a community—the latter realized through cost savings and damage loss avoidance—associated with new capital investment into resilience to those generated by the status-quo. This report provides a means to increase the capacity of communities to objectively and effectively compare and contrast capital investment projects through consideration of benefits and costs while maintaining an awareness of system resilience. Topics related to non-market values and uncertainty are also explored.

Approach

The guidelines in this report are designed for use in conjunction with the Planning Guide by providing a mechanism to prioritize and determine, based on supporting community social needs, the efficiency of resilience actions. The Planning Guide provides a methodology for communities to develop long-term plans by engaging stakeholders, establishing performance goals for buildings and infrastructure systems, and developing an implementation strategy.

5. Barter

Barter is a system of exchange where goods and services are traded directly for other goods and services without using money as an intermediary. In a barter economy, individuals or entities exchange items they possess for items they need or want. This system has been used by various societies throughout history, especially in pre-monetary or less developed economies.

Here's how the barter system typically works:

- Double Coincidence of Wants: For a successful barter exchange to occur, both parties involved must have something the other party wants and vice versa. This is called the "double coincidence of wants." In other words, each person must want what the other has to offer.

- Negotiation: Once two parties with complementary wants identify each other, they negotiate the terms of the trade. This negotiation can involve haggling over the quantity, quality, or other aspects of the goods or services being exchanged.

- Value Comparison: Determining the relative value of items being exchanged can be challenging. People often rely on their perception of the worth of the items, which can lead to disagreements and disputes.

- Division of Goods: In some cases, barter may involve multiple goods or services being exchanged in one transaction. This can complicate the exchange process, as it requires all parties to agree on the terms of the trade.

- Limitations: Barter has several limitations and challenges, including the difficulty of finding a trading partner with precisely matching needs and wants, the lack of a common unit of account (like money), and the inefficiency of large-scale trade. It can also be cumbersome when dealing with goods that are perishable or difficult to transport.

- Indirect Barter: To overcome the limitations of direct barter, some societies developed indirect barter systems. In these systems, an intermediary item, often referred to as "commodity money," would be used as a medium of exchange. For example, ancient societies might use items like grain, livestock, or precious metals as a common medium of exchange.

- Transition to Money: The inefficiencies and limitations of the barter system eventually led to the development of money. Money serves as a universally accepted medium of exchange, a unit of account, and a store of value, making trade more efficient and convenient.

In modern economies, barter is not the primary means of exchange. Money, in the form of currency and digital transactions, has largely replaced barter due to its convenience, divisibility, and widespread acceptance. However, barter is still used in some situations, such as in small-scale or local exchanges, as a form of informal trade, or in situations where currency is not readily available.

5.1. Game: The Swap Challenge

Duration: Approximately 1 hour

Number of Players: 6-8 adults

Objective: To simulate a lighthearted barter economy where participants trade items and services creatively while experiencing the challenges and joys of direct exchange.

Materials:

- A variety of small, random items (e.g., toys, kitchen gadgets, trinkets)

- A timer or stopwatch

- Small cards or slips of paper

- A bowl or container for drawing slips

- Play money (optional)

Game Rules:

1. Set Up:

- Place the random items in the center of the playing area.

- Prepare small cards or slips of paper with fictional "barter values" for each item. These values can be represented in a playful way (e.g., three chicken dances, five silly jokes, or one air guitar performance). Place these cards in the bowl.

2. Start the Barter Challenge:

- Each participant draws a slip of paper from the bowl, which reveals the "barter value" of the item they receive.

- Participants then have a limited time (e.g., 5 minutes) to barter, trade, or negotiate with others to acquire items with a combined "barter value" equal to or greater than their own item's value.

3. Trading and Negotiation:

- Participants must find others willing to trade their items or services to reach the desired "barter value." They can negotiate creatively, using humour or unique offers to persuade others.

- Encourage participants to use their imagination and engage in fun negotiations. For example, someone might offer to sing a song in exchange for a rubber duck or perform a magic trick for a set of colourful beads.

4. Time's Up:

- When the time is up, gather the participants to see how successful their barter exchanges were. Ask each player to share their final item and explain the trades they made to reach their target "barter value."

5. Prize or Reward:

- Offer a small prize or recognition for the participant who successfully reached their target "barter value" with the most creative or entertaining trades.

6. Reflection:

- After the game, discuss the challenges and joys of bartering without money. Reflect on the concept of the "double coincidence of wants" and how creative negotiations were used to overcome it.

- Share some fun anecdotes and laugh about the unique offers and trades that took place during the game.

Optional Variation:

To add an extra layer of complexity and strategy, you can introduce play money. Participants can use this money to sweeten their deals, make multiple trades at once, or even pay off "barter value" debt if they can't find a direct trade.

This game combines the values of barter, such as negotiation, value comparison, and creativity, in a playful and entertaining way. It encourages participants to think outside the box while experiencing the challenges and humour of direct exchange. Plus, it's a great opportunity for laughter and lighthearted interaction among friends or colleagues.